Neil Jordan ponders The Butcher Boy

Oscar-winning writer and director Neil Jordan swept into town this spring with his fiery young protégé, Eamonn Owens, in tow to present the Toronto premiere of The Butcher Boy, his latest and possibly darkest film out of Ireland. Based on Patrick McCabe’s best-selling novel of the same name, Jordan’s distinctive screen adaptation won the Silver Bear Award at the Berlin Festival, and fifteen-year-old Owens received a Special Mention for his powerful debut performance as the precocious Francie Brady.

Oscar-winning writer and director Neil Jordan swept into town this spring with his fiery young protégé, Eamonn Owens, in tow to present the Toronto premiere of The Butcher Boy, his latest and possibly darkest film out of Ireland. Based on Patrick McCabe’s best-selling novel of the same name, Jordan’s distinctive screen adaptation won the Silver Bear Award at the Berlin Festival, and fifteen-year-old Owens received a Special Mention for his powerful debut performance as the precocious Francie Brady.

Surrounded by a circle of critics, the enigmatic Irish director casually sprawls on a couch in his sunny Yorkville hotel suite answering questions ad nauseam about his latest cinematic achievement. Smiling shyly and squirming in his seat like an overgrown school boy, Jordan seems uncomfortable in the limelight. He bides his time, as though pondering every syllable of each query. Luring the mystery man out from behind his director’s mask is a challenge relished by all but one seasoned critic (who wishes to remain anonymous). “Jordan is a difficult interview,” she pronounces during the break. “You have to goad him with a cattle prod before he’ll talk about his work, and when he finally says something, it’s the same stuff he’s been feeding all the other media.” Arriving partway through the screening, she quickly concludes The Butcher Boy is a typical “boy-goes-bad” slice ’em up flick — which it is not. There’s no Jason-meets-Freddy or Halloween schlock in this butcher shop. It’s an authentically Irish tale right down to the bolloxing bogmen, black-skirted priests and archaic Co. Monaghan dialect.

While The Butcher Boy is definitely not everyone’s cup of tea, it is far from being a slick Hollywood slice-and-dice horror. Shot on location in the provincial town of Clones, Jordan’s film is a dark comedy that cleverly combines art and realism with old fashioned voice-over narrative (by Stephen Rea). Unlike most literary adaptations, it’s also miraculously true to the spirit of McCabe’s novel. “I found the book very cinematic in a strange way, even though it’s stream of consciousness,” Jordan says. “It’s a story about a Dennis the Menace type who sees himself as a superhero. I thought it one of the best accounts of childhood I’d ever read.”

While The Butcher Boy is definitely not everyone’s cup of tea, it is far from being a slick Hollywood slice-and-dice horror. Shot on location in the provincial town of Clones, Jordan’s film is a dark comedy that cleverly combines art and realism with old fashioned voice-over narrative (by Stephen Rea). Unlike most literary adaptations, it’s also miraculously true to the spirit of McCabe’s novel. “I found the book very cinematic in a strange way, even though it’s stream of consciousness,” Jordan says. “It’s a story about a Dennis the Menace type who sees himself as a superhero. I thought it one of the best accounts of childhood I’d ever read.”

Jordan was so impressed, he asked McCabe to write the screenplay. “Since Pat’s a friend of mine and we come from the same environment, it just happened naturally. In a sense, I was recreating his childhood. I cast him in the movie [as Jimmy the Skite] and shot him in the town he grew up in … I wanted him as involved as possible. He wasn’t used to writing script, though. His first draft was too long, so I asked him to shorten it, which he did. But when I saw all the changes, I had to say, ‘Sorry, Pat, but I don’t remember asking you for a whole new novel.’ He was worried about hinging the whole film on voice-over, so we ended up writing together.”

The result is a brilliantly performed look at the effects of sixties pop culture on an unstable small-town boy growing up in the underbelly of Irish culture. And yes, Francie does go mad and chop Mrs. Nugent (Fiona Shaw) to pieces, but she deserves it — or so I thought. Not in Jordan’s opinion:

“It was very important that there should be no villains in the piece, because you can easily say, ‘Okay, Francie’s the way he is because those ladies in the shop treat him consistently horribly.’ Then you’d be able to blame them. Even Mrs. Nugent does nothing wrong to the boy in the end. She just doesn’t want him in her company. It is important to see very clearly that it is the child’s mind that drives him, that there is some disturbance in Francie’s interior world and not any particular character, not even the priest who half abuses him. The entire adult world around him is well meaning. They just don’t notice his specific trauma.”

“Then why is Francie so mad at the ‘well-meaning’ adult world?” I ask. “He had a hard upbringing and must find compensation for the series of disasters that happened to him,” Jordan explains. Francie lives in an imaginary world to escape a life of poverty and shattered dreams. His father, Benny, played by Stephen Rea, is an alcoholic jazz musician down on his luck; and his mother, played by Aisling O’Sullivan, is a frail woman who slowly drifts into madness and suicide.

“Actually, Francie is always ahead of the adults,” Jordan continues, as though lecturing a class of attentive school kids. “Even the psychiatrist. But he’s manic, obsessive and estranged and given to grandiose behaviour. For instance, when his blood brother, Joe [Alan Boyle] gives the goldfish to young Nugent [Andrew Fullerton], the son of his nemesis, Francie perceives it as the ultimate betrayal. That’s why he tries to win as many goldfish at the carnival as he can … because he thinks it’s the key to his friend’s heart, to winning him back.”

Finding the right Francie Brady was possibly Jordan’s greatest challenge. “I had a team turning Ireland upside-down. We did read-throughs with 2,000 children. It got to the point where I thought we wouldn’t be able to make the movie because there’d be no point without the right child. Eventually we found Eamonn Owens in the tiny town of Killashandra, Co. Cavan, working in his parents’ vegetable shop. He’d never acted before, but when I began working with him, I realized he would be marvellous. I cast his young brother [Ciaran Owens], as well. And his friend Joe goes to the same school. I’d like to work with Eamonn again. It’s very rare to come across someone with so much energy and power.”

Jordan’s new young star may take to the screen like a fish to water, but even he has limitations. “The most challenging scene for me was with Milo O’Shea as the [homosexual] priest in the reform school,” says Owens,” because I couldn’t identify it with anything in my life to know what to do in the scene. But Neil was brilliant, and Milo O’Shea was fabulous. He knew to perfection what he was meant to be doing. It was easy after a while, even though I was quite worried about the scene.” Overall though, Owens has been having tremendous fun. “I particularly enjoyed the scenes in the house with Stephen Rea, especially when he broke the TV set. Seeing him kick in the screen was very entertaining. He’s extremely funny.” After his debut with Jordan, Owens took a role in John Boorman’s Irish gangster film, I Once Had a Life. “I hope I’m offered more parts in the future. If I continue to enjoy acting, I’ll study it in school.”

For Jordan, working with Owens effected a kind of catharsis. “It was a weird experience for me, because Eamonn looks like me when I was his age, especially in the altar boy’s costume. I remember growing up in Ireland at the time and being told I was surrounded by ghosts all the time. The Catholic thing is very strong there, very basic in a very superstitious way. As a kid you were told that voices would speak to you from the sky at any moment. I was terrified by the possibility that one of these figures would appear to me and say, ‘Neil, you are the one. Come and work with us. Wear a black skirt like us, Neil.'”

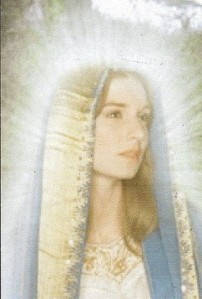

Sinead O’Connor as The Virgin Mary

Jordan’s apocalyptic scenes and special effects are macabre, gritty and disturbingly funny manifestations of his own childhood fears. “I remember seeing the nuclear blast on TV and being taught what to do in case of a nuclear strike. ‘Get under the bed.’ we were told.” Amidst all the gory Goth, Sinead O’Connor’s Virgin Mary shines like a glossy Hollywood neon goddess. “It’s the way the religious statues and pictures appear in real life. They’re very gaudy. I love religious art, the Hindu gods and Indian spirits. If you saw the Virgin Mary, she’d appear very bright, with a big spotlight behind her. I was going to make Marilyn Monroe the Virgin Mary, the way you would imagine it in the Hollywood way. Sinead looks more like the ‘real’ Virgin Mary in the iconography I grew up with: the beautiful profile, dark hair, sallow skin, lovely bone structure. Just like Sinead.”

The Virgin Mary’s language is pretty upbeat for a religious icon — she uses the “F” word — and may offend those with delicate sensibilities. “It didn’t offend them in Ireland, Jordan says. “Maybe it will in the States, but that’s how Francie imagines her talking, and she talks in his voice.”

A drawback for the film is the use of authentic dialect, which is very confusing for an audience unfamiliar with Irish colloquialisms. It may take a good ten minutes just to grow accustomed to the accent. “You’ve got a choice,” Jordan insists. “You either mess it up and make it mid-Atlantic, in which case it doesn’t have any integrity at all, or you make it as accurately as you can for the people involved and hope that the audience will reach it. For me, it’s better not to compromise so that the power and strength of the movie is more intense. I think if you tried to flatten out this adaptation and make it acceptable all over the world, however you imagine it, you would destroy the book entirely.” Jorden is undoubtedly right, but the Co. Monaghan dialect makes voice-over a necessary evil in this film, for North Americans at least. Another option would be to add subtitles.

The language barrier apparently has had little effect on audiences in England and Europe, however, and Jordan remains in awe of how well The Butcher Boy is being received across the pond. “It’s been praised very highly, and it’s getting quite a significant audience for the kind of movie it is. I think movies are becoming a bit too anodyne.”

Whatever the reasons his disgruntled critics attribute to his self-reflexive time-lags, Jordan has not lost his Midas touch. His heady cast of professionals, amateurs and authentic townsfolk, his juxta-positioning of location and studio filming with surrealistic special effects and unique use of religious symbolism in The Butcher Boy recall the art films of Bergman and Fellini, but from a distinctly Irish point of view. Following in the footsteps of these and other art house icons, Jordan has carved out a body of work and a stock troupe of actors headed by Stephen Rea.

While behaving more like an angry young author than a fervid film director may be a thorn in the side of some critics, Jordan wears both hats with aplomb. Judging by his collection of screenplay awards, his writer’s hat fits remarkably well. So what if he’s crammed it into his back pocket alongside a crumpled Dennis the Menace comic and old chewing gum?

Celtic Curmudgeon Arts & Entertainment Review, 1998